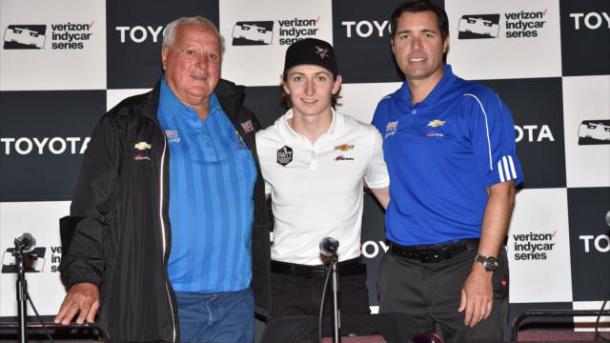

‘We made it to IndyCar’: Zach and Roger Veach’s hard road to open-wheel’s summit

Bob Kravitz | The Athletic

The Comet go-kart had a purple chassis, white bodywork with purple and silver stickers on it, and it was the most beautiful thing Zach Veach had ever seen. It was 2007 and he was 11 years old at the time, having begged and pleaded for his very own go-kart since the time he was 4 and had told his father, Roger, he wanted to be an IndyCar driver someday.

Roger Veach already had lived out his motorsports dream, becoming a champion tractor puller, traveling the country with Zach as they left their hometown of rural Stockdale, Ohio, and went from town to town and collected trophies. One trip, they drove 26 hours out west, unloaded, waited six hours, competed for eight seconds, won the competition, loaded the truck back up and drove 26 hours home.

Zach absolutely loved those times, the chance to bond with his father, to help in the garage, which mostly meant wiping down the wheels and cleaning the dirt off his father’s truck’s chassis. But from the very first time he saw the Indianapolis 500 on TV at a very tender age, he was committed to following his father into the motorsports realm and becoming an IndyCar driver.

“It was just the look of the car, and seeing the Indy 500 on TV when I was maybe 3 or 4, just seeing how big the event was, it made these drivers look almost superhuman, getting into cars and defying the odds, it made me fall in love with the whole thing,” said Veach, the Andretti Autosport driver who qualified 17th for this Sunday’s 104th running of the Indianapolis 500. “I thought that was the coolest job in the world, and my dad told me, `You can do this if you really want it,’ and it changed my life. After that, I woke up every day saying I want to be a race car driver.

“It spoke to me, for whatever reason. I wanted it more than anything. I’ve never really been into any traditional stick-and-ball sport and I never fit there, but the first time I got into a go-kart, it fit.

“… At the end of the day, I fell in love with motorsports because of what he (Roger) was doing. At some point along the way, I was watching my dad in a firesuit and thinking, `You know, someday I want to be just like him.’ To me, my dad was a superhero. He wasn’t driving an IndyCar, but he was wearing the same cape.”

Roger fed his son’s dream from the beginning, telling him he could do what he set his mind to. But when Zach was 11, they were making the long drive out to a western outpost for a tractor-pulling event and passed by their nearby go-kart track in Circleville, Ohio. Sitting in the passenger seat of their tractor-trailer semi, he turned to his dad and said:

“Dad, if I don’t start any sooner, I’m not going to get my shot to go to IndyCar,” he told Roger. Zach noted that there were already 5- and 6-year-olds out there, that they were getting a competitive leg up on him, and it was time to go all-in.

At that point, Roger could have said, “Yeah, well, just play with your GameBoy and we’ll talk about it later.”

But that’s not what happened.

One week later, when Roger himself was on the road about to go racing, everything changed.

“I called home and was checking on (Zach) and he was just really upset; he didn’t think he was ever going to race,” Roger said this week at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. “So as I was getting strapped in the truck that night, I told my crew guys, `Hey, this is the last time I’m going to run.’ They kind of giggled and said, `Yeah, last time this year,’ and so I made my run and there was a guy who always bought my equipment because I was building a lot of new stuff and as I was going back to the pits, I saw him and said, `Hey, Andy, you want to buy this truck?’ He goes, `Yeah, you building a new one?’ `Well, not exactly.’

“So that was a Saturday night like 10 o’clock. By Monday morning at 9, the transporter was sold, all the spare parts were sold, the truck was sold. And I bought a go-kart. I told Zach, `I’ll take you to the track anytime you want.’ Anytime turned into every day. …”

Roger had lived his dream, and now it was time to help Zach pursue his.

“It was like all of my father’s pulling stuff went away and then we got to the garage, and all that’s in there is this tiny junior go-kart and we’re trying to figure out how to put it together,” Zach said. “I wish at that age that I had appreciated the sacrifice he’d made for me; it took a few years before I understood how special that was.

When you’re that age, all you’re thinking about is `How do I get better so one day I can drive an IndyCar?’ Now that I’m at Indy, I think about the day my dad and I spent showing up in a pickup truck at the go-kart track with no plan, no idea, no nothing, but it was the most fun I’ve ever had, just genuine moments with my dad I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

Six days a week, Roger and Zach were over at the Circleville track, running laps, one after another after another.

“We ran so many laps in the spring before the season started that we literally wore the chassis out before the first race,” Zach remembered. “We ran it like that the first couple of races until we realized it was falling apart. So we threw it in the trash and bought a new one and kept going.”

Roger had given up his tractor-pulling career – he also has an IT firm he continues to run to this day – but he was completely focused now on making Zach’s outlandish IndyCar dream come true. And not in a helicopter or Little League dad sort of way. He was a coach, true, but mostly he was his greatest supporter, financially and spiritually.

Understand, motorsports are expensive, crazy expensive. Some drivers are second- and third-generation drivers, an Andretti or a Rahal, and have the means and the access to the sport. Some families can make the investment. But the Veach family was middle class, and it took everything Roger and his first wife had to feed Zach’s desire to drive race cars. There were second and third mortgages. There were massive loans, some of which have not yet been paid off. There was pressure on Roger and the whole family.

“It’s been a tough journey,” Roger said, shaking his head. “There were times I didn’t think we were going to make it. There were times I thought I was going to lose my (tech) business.

“… It was just like having a 10-ton weight on your back. I mean, there were times that I was thinking, `Man, I don’t know how we’re going to keep going.’ But it seemed like every time we got in that position, God just opened another door for us and took care of it. There were times that everything I was making was going into it.

“… I had a friend ask me one time, `Roger, why are you doing this? The amount of money you’re spending, you can retire comfortably and not have to work the rest of your life.’ I said, `Yes, but you know, this is what (Zach) wants to do. He’s my kid. I made him a promise. I made him a promise that day on the back of the pickup truck. I told him, `As long as you don’t stop working, I’ll never stop working. And he never quit working. …’ ”

At the time he got his go-kart, Zach didn’t completely understand the sacrifices his father had made for him, but over the years, he has gained a full appreciation for what Roger gave up on his behalf.

“He’s set the bar of being a father too high,” Zach said, laughing. “One thing I’ve thought about is, I’m 25, so probably sometime in the next five years I’ll start thinking about having a family. The sacrifices my dad made for me is something that’s been … inhuman. My dad has never put himself first. He’s taken a really big risk, put the company at risk, his livelihood at risk. The debt, we’re still paying off a mountain of it to stay where we’re at. I look back now and ask, `Why, why did you take this big risk?’ I’m just really lucky my dad believed in me and by him believing in me, it made me believe in myself. Without him, I wouldn’t be here now.

“Struggling the way we did, it makes you appreciate everything so much more. Nothing has come easy. I’ve always been an underdog. I’ve had to work harder than most to be successful, and that’s never going to stop. I’m always going to keep busting my butt to close the gap – if there is one.”

The bullying was incessant.

Zach is currently listed at just 5 foot 4 and 135 pounds soaking wet, and that’s after a fitness regimen designed to help him gain size. When he was little, he was, well, very little. He was so small, his father, also a man of small stature, used to have to outfit Zach’s cars with a carbon-fiber box of sorts so that his feet could reach the pedals.

As he grew older (but not much bigger), the bullying became relentless. In junior high and high school, if you’re not an alpha, you end up a target. Here he was, this undersized kid with oversized racing dreams, consistently finding himself in the crosshairs of bigger kids with bad intentions.

“I had to go to school and pick him up one day because he’d had a tooth knocked out,” Roger recalled. “He told me he fell. But that’s not what happened. A kid had come up from behind him and shoved his head, face-first, into the desk.”

Zach is very outspoken on the subject, hoping his story will resonate with those who are bullied, and even those who are doing the bullying.

“It was tough, I’m not going to lie,” Zach said. “I think my whole life, I’ve always dealt with a little bit of self-doubt because of those early years. Those are your formative years and you’ve constantly got people telling you that you’re not good at anything. It’s been part of my motivation to keep proving to myself and other people that I am good enough.

“I was lucky to have had an incredible support system, but when I was getting bullied in school, it got to the point where I wanted to quit racing. Kids were making fun of it every day. I had my dad and mom, who were super supportive, and I had two or three teachers who thought it was the coolest thing in the world, and that’s why I speak out a lot about bullying. I got to the point where I was going to quit doing the one thing that I felt I was meant to do. So I worry about other kids who are bullied who don’t have the kind of support system that I had. I want to make my voice heard in the loudest way that I can to keep those kids motivated.”

Zach is not only outspoken about bullying; he also is the national spokesman for FocusDriven, which aims to stamp out distracted driving, has released a book, “99 Things Teens Wish They Knew Before Turning 16’’ in 2011 and was named to CNN’s list of “Intriguing People” in 2010.

Said Roger: “He’s always been one of those kids who feels it’s his responsibility to deal with something. It was tough, absolutely … But the way he handled it, even though he was little, he always stood up for himself. He was bullied pretty badly … but I don’t think he’d be as resourceful now as he is had he not gone through it. Even though it was a bad experience, it molded him and taught him. I had it in school, too, but you’ve got to work through it. And he wants to let people know that this doesn’t define you and you can overcome it.”

Veach is in the final year of a three-year contract with Andretti Autosport, and he’ll still looking to win a race or reach the podium. But at every step up the ladder to IndyCar, he has proven himself a very capable and promising young driver. He had six wins in the Indy Lights series; in a six-year Road to Indy career, he earned 13 wins, 14 poles and 39 podium finishes.

Qualifying this past week was a bit of a challenge – his Honda-powered Andretti car didn’t have the same success as four of his teammates, who finished first, second, third and fourth in qualifying – but Veach, who is 25, is a factor.

He is not a favorite this coming Sunday, not by any stretch of the imagination, but he’s here and Roger is here – he’s only missed two IndyCar races in Zach’s career, and will watch the race from the roof of their motorhome – and while winning would mean the world, these moments together, many thousands of moments they’ve spent together through the years, they mean even more.

“By the skin of our teeth and a little bit of luck, we made it to IndyCar,” he said, emphasizing the `we.’ “We’re just a couple of guys from a really small farm town in Ohio at one of the biggest, if not the biggest, race in the world.

“Now that I’m older, I’ve said to him, `I don’t think I can ever make the same sacrifices you’ve made,’ and he teared up and said, `Well, we look pretty similar, so if one day your face is on that (Borg-Warner) trophy, it’ll be a little bit like having mine on there, too.’”